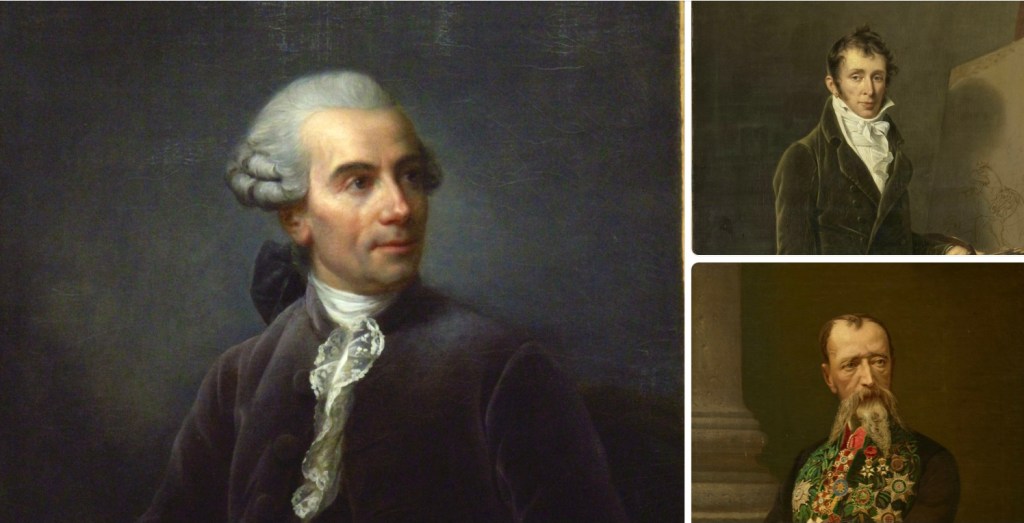

Four Generations of Painters Spanning More Than Three Centuries (1689–1863)

Written by: Claudia Dijkstra Crommelin*1

The first generation of this celebrated family was Antoine Vernet, born in Avignon in 1689 and died in 1753. Antoine was a painter of landscapes and a decorator of carriages. He had 22 children, of whom only 13 survived; four became painters. His son Joseph (1714–1789), also born in Avignon, became the most famous of all the painting children. As soon as Joseph was old enough, he moved to Paris but soon decided to leave for Rome, a city where many artists and painters lived and worked in the 18th century. While working in Italy and gaining recognition there, Joseph considered sending paintings to the Salon in Paris, regularly held at the Louvre, in case he later decided to return. In 1750, after 20 years of living in Rome, he made the decision to return to France; being concerned about his father’s health was another reason for him to return. Although renowned and recognised in Rome, he was aware that he might still have to earn his place in Paris. However, this was unnecessary, as even the Pope regretted his departure and issued an order forbidding any painting by Master Joseph Vernet from leaving the country.

Back in France:

Barely settled in, Joseph received an invitation from the Marquis de Marigny, who was, in fact, the brother of Madame de Pompadour, the famous mistress of King Louis XV. La Marquise was a woman of taste, arts, and letters, and she supported many artists. Joseph Vernet’s friend, Denis Diderot (1713–1784), was one of them. Thanks to this friendship, Joseph was invited by the Marquis de Marigny to hisprivate mansion. In reality, this invitation came directly from the King, who wanted to commission Joseph Vernet to paint all the ports of France. Joseph happily accepted the task, unaware that it would take him eleven years to complete. Becoming a painter for the King meant an important privilege, a steady income, and accommodation in one of the galleries of the Louvre.

Carle Vernet’s Childhood:

In those days, the Louvre was far from a luxurious place. The building offered only simple spaces within a large gallery, with few, if any, windows. These spaces were separated by planks and curtains. Many great painters lived side by side under these modest conditions. For Joseph, this was not a problem at all; he was very happy with the nomination. In October 1753, he left with his wife, Virginia Parker, and their newborn son, Livio, for Marseille, the first port he painted. Five years later, they were still travelling along the coasts of France. In 1758, Joseph, aged 44, became the father of a second son, Antoine Charles Horace Vernet, later known as Carle Vernet, who was born in Bordeaux.

Carle was still very young when things changed dramatically for the Vernet family. Around 1762, the King began paying less and less, and Joseph’s contract was renegotiated. Some of the ports were now controlled by the English, and as Joseph grew older, he requested an interruption of his contract. This request was accepted, and on July 14, 1762, the Vernet family returned to Paris, arriving in a carriage that King Louis XV had sent as a reward for Joseph’s paintings of the ports over the years. Soon, the family settled in the galleries of the Louvre, where Carle would spend his entire childhood. The young children mostly played under their mother’s supervision, and she ensured they were always very well dressed. Therefore, it makes sense that Carle Vernet continued to dress elegantly throughout his life.

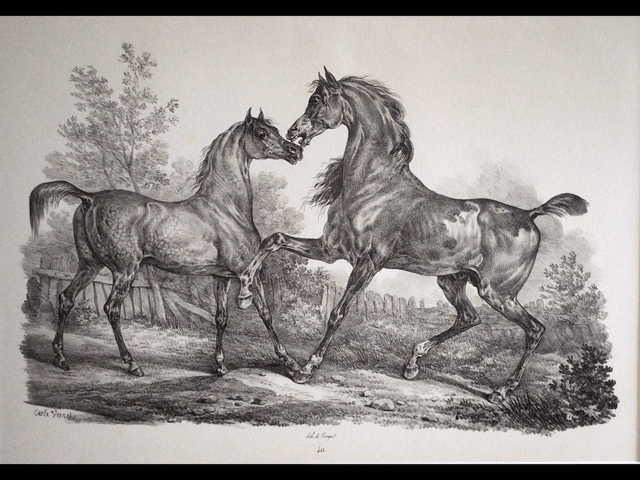

Carle Vernet Discovers Horses:

Carle began showing an interest in horses when he was just five years old.As it was customary in those days to keep very detailed diaries, a nice story about the six-year-old Carle drawing a horse has been preserved. One day, his father was invited by Monsieur Marraine, the manager of the King’s buildings. Being a proud father, he decided to bring Carle along and asked his son to draw a horse. Carle started too low on the paper, leaving no space to draw the horse’s legs. While his father grew irritated by this mistake, the young boy quickly finished the horse’s body, then began drawing the legs. Suddenly, with a single stroke of the pencil, he completed his sketch by drawing water, allowing his horse to proudly take a bath. Joseph exulted with joy and probably some relief. This anecdote perfectly illustrates Carle’s inventive spirit, creative mind, and his ability to surprise his audience.

Meanwhile, the Vernet family still lived at the Louvre, by an ordinance of the King—a privilege reserved only for the best artists in France. Twenty-six families lived there, with their children frolicking around. It is more than likely that some of the painters’ works were accidentally damaged by the playing children and by adults enjoying parties where alcohol was probably involved as well. Young Carle was by far his parents’ favourite, as he was born sickly and delicate, thus requiring extra care. This might have been the reason he was not sent to boarding school.

Unfortunately, Carle’s mother suffered from a mental illness, and Carle and his little sister, Émilie, were being looked after by a valet called Saint-Jean. This loyal valet stayed with the family throughout his life and later also cared for Carle’s children. As such, this man played a very important role in the family.

In the meantime, the Vernet family enjoyed a comfortable life. In 1765, Joseph earned a considerable amount of money from an investment, which he bequeathed to his children. A little later, he profited a second time, again sharing the gains with his children Livio, Carle, and Émilie, thereby ensuring each child had an annuity of 190 pounds—a substantial sum in those days. As Joseph’s fame and fortune grew, his family was able to move to a more comfortable accommodation very close to Paris. After relocating several times to different areas around the city, Joseph finally decided to purchase a nice country house in Rueil (now Rueil-Malmaison), while also maintaining his studio at the Louvre, thus staying close to his fellow painters.

But then fate had other plans, and young Carle fell ill with smallpox. In those days, without any available treatment, the disease was often fatal. After an extremely worrying time, Joseph managed to save his son. Aware of Carle’s interest in horses, he gave his son two large volumes on cavalry.

Carle and His Masters in Painting:

Thanks to his father’s fame, Carle met many renowned men, now recognised as the great thinkers of the 18th century. During a trip to Switzerland and France, he was introduced to the eminent writers and philosophers Voltaire (1694–1778) and Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778).

Carle Meets his First Teacher:

In July 1769, at only eleven years old, Carle entered the studio of his first teacher, Nicolas Bernard Lépicié (1735–1784). Lépicié was a well-known and gifted teacher but had some unusual habits. One of these was dressing like a monk, which could have been somewhat frightening to his mostly very young pupils.

Shortly after his painting lessons began, Carle wrote a letter to his father describing his daily routine: “Lessons start at 5:30 a.m., with drawing all day—one week with models and one week outdoors.” Remarkably, the young boy did not complain at all about the long working days.

Carle’s earliest known painting is dated November 1771, when he was 13 years old. His teacher painted several beautiful pictures of both Carle and his sister, Émilie. Carle met many of his father’s colleagues and friends, which made it easy for him to introduce himself into the higher Parisian circles.

A 16-year-old Adolescent:

Carle became increasingly independent from his father, and it was only natural for him to pursue his passion for horses. His fortune came unexpectedly with the establishment of an Equestrian Theatre. In 1782, the Englishman Philip Astley arrived in the area. This theatre became an important place for Carle, as it provided the perfect opportunity to study many horses in various positions during training. During the performances, the theatre was illuminated by 2,000 candles, which was something considered extraordinary

In the meantime, Carle Vernet had become a fashionable young man with a kind face and distinguished looks. His manners and skill in horsemanship also made him highly sought after in society. There is little doubt that he was known throughout Paris as an excellent and elegant rider.

All this time, Carle continued to work for his former teacher, Lépicié, and frequently visited the Royal Stables. There, he had access to the Riding School and the training grounds at the Tuileries, which provided him the opportunity to observe and sketch the highest-quality horses.

Prix de Rome:

The Prix de Rome was a prestigious art scholarship established in France in 1663 during the reign of Louis XIV. It was created to support promising artists by enabling them to study in Rome at the Villa Medici. In 1779, Carle entered this competition and received the second prize, which was not sufficient to earn a stay in Rome. The Prix de Rome was known for its strict rules: the subjects were revealed only at the very last minute, and competitors were separated from each other by partitions.

It took another three years for Carle Vernet to win the first prize. In a letter dated August 1782, one of the judges wrote: “I have just left the Academy where we judged. Joseph Vernet’s son won first prize. The whole Vernet family was in tears.” This meant, of course, that Carle could finally go to Rome.

1782: In Rome

In the autumn of 1782, Carle indeed left for Rome, taking an impressive amount of clothing—24 new shirts, 23 old shirts, 36 silk handkerchiefs, and the list went on. Upon his arrival, Carle was received by the director of the famous institution, the Villa Medici, himself. Unfortunately, Carle’s stay in Italy did not prove to be beneficial. He had to say goodbye to his young girlfriend in Paris and was overcome with melancholy. Since his father had lived in Rome for 20 years, his son was welcomed everywhere he went, but nothing seemed to cheer him up. He found himself completely lost and even forgot the reason he was there, which was to paint.

Finally, he saw turning to religion and becoming a monk was the only solution. The director of the school, a good friend of Joseph’s, decided to inform Carle’s father about his lost son. Joseph became very worried, which led to correspondence between Joseph and Carle’s tutor. Joseph urged Carle to return to France immediately, but his letters went unanswered. Determined, Joseph rushed to Rome to fetch his son himself. He arrived just in time to prevent Carle from taking the habit and brought him back to Paris.

Back in Paris:

Carle quickly readjusted to Parisian life, especially after his father gave him a horse. At that time, people typically rode the calm, heavier French saddle horses, but the new fashion for English blood horses spread rapidly, even though these horses required skilled riders. Since Carle was known to be a good rider, he received his first high-spirited horse. The horse was stabled on the estate of the Duke of Chartres.

It was well known that Carle was welcome at the Royal Palace and had also been admitted to the intimate circle of the Duke of Orleans. The latter invited him on many hunting trips, during which Carle took the opportunity to study and sketch the horses. This is the reason so many hunting paintings and prints are attributed to Carle.

As the well-known art critic and historian Amand Dayot (1851–1934) stated many years ago: “Never did a painter love the Horse with more passion than Carle Vernet, which he knew by heart from head to tail.”

In 1784, Carle began searching for a new teacher and ultimately decided to study under Joseph Vien. Master Vien (1716–1809) held the prestigious position of Premier Peintre du Roi which translates to court painter, which he occupied from 1789 to 1791. Being so close to the King could prove advantageous for the 26-year-old Carle Vernet. In the meantime, there was a great deal of activity in the galleries of the Louvre. One of the new arrivals was the well-known painter Jean-Michel Moreau (1741–1814), who also brought his entire family with him. Naturally, they met the Vernets, and Carle soon noticed the presence of Moreau’s pretty daughter, Catherine Françoise, called Fanny, born in 1770. Carle and Fanny married in 1787.

The Académie Royale and the École des Beaux-Arts:

In 18th century paintings, depicting a man on a horse meant portraying him in his finest clothes and positioning him on a horse to pose—often even on a fake wooden horse. Carle Vernet did not see it that way. He believed that: “Since we paint a man as he is, why not paint horses as they are?” To begin his new approach to painting, Carle returned to the Royal Stables. After spending a long time studying the horses again, he locked himself in his studio, refusing to let anyone in not even his father or his father-in-law, both experienced painters. However, fearing possible criticism from them, he kept the door closed. After several days, his father and future father-in-law forced the door open and entered the studio. When they saw the painting Carle had hidden, his father exclaimed, “Carle, now you are a true painter!” According to the story, this was also the moment Moreau granted him his daughter’s hand in marriage. This painting, The Conqueror of Perseus (168 BC), measuring 4.30 x 1.30 meters, was exhibited at the Salon in Paris in 1789. It is now owned by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. This painting opened many doors for Carle Vernet, and he was elected as an approved member of the Académie Royale, which was founded by Louis XIV in 1648.

In 1793, when Carle was thirty years old, the doors of the famous Académie were closed. However, two years later, the École des Beaux-Arts opened. This art school in Paris still exists in the same beautiful building. Joseph was already a member of the Académie, but this was the very first time a father could welcome his son! During the very formal admission ceremony, father and son forgot the rules of etiquette and threw themselves into each other’s arms, applauded by the assembly. It was truly a historic moment.

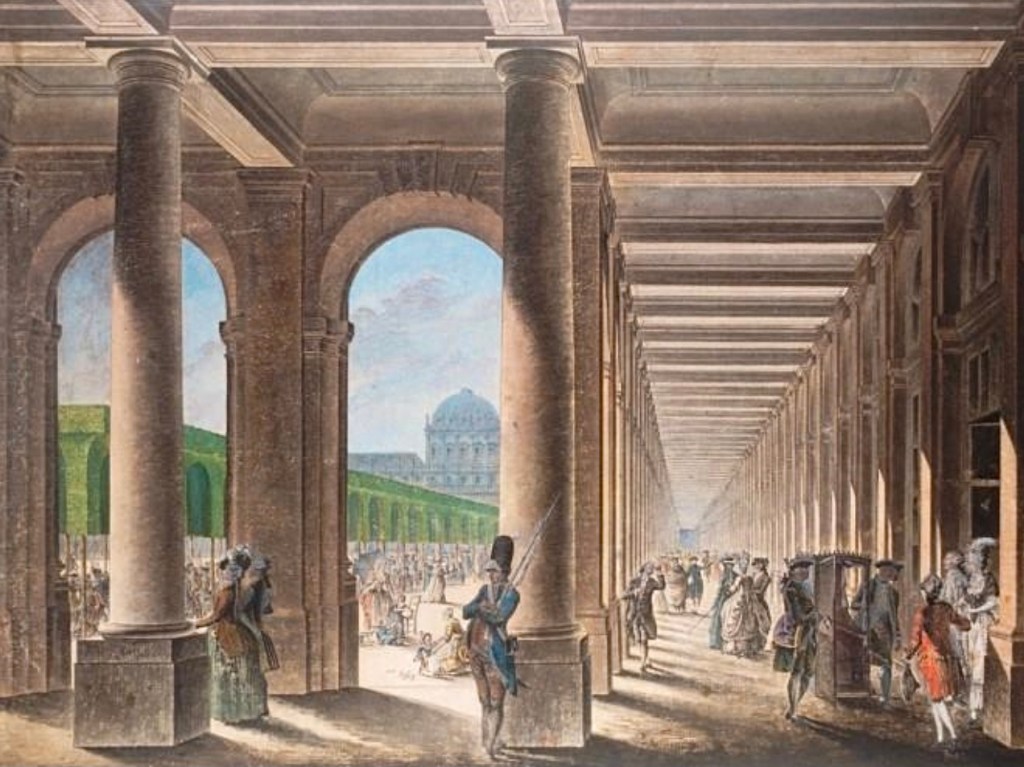

Leisure time was often spent at the Tuileries or the famous Café de Foy, founded in the early 18th century and the only café at the time where tables were allowed to be set up in the garden. The café became Carle’s headquarters, where he went almost every day to meet his friends.

Many of the meetings in preparation of the French revolution were held in this Café as well. It was also the place where he met the master painter/engraver Philibert-Louis Debucourt (1755-1832). Vernet and Debucourt worked together on at least 80 works.

For a while, Carle’s father had to become his son’s banker, as Carle was increasingly leading the life of a dandy and spending too much money. In Carle’s account book, for example, the purchase of a mare is recorded. A little later, he sold the same mare at a huge loss of 700 pounds, a fortune in those days. However, as his father’s memory began to fail not long after, Carle had to grow up and manage his own finances. At the same time, Carle’s fame grew, and even the Duke of Orleans commissioned a hunting scene. In those days, it was not at all uncommon for Carle and his father Joseph to receive the King and other members of the Royal family in their studio. Around that time, the fourth generation of Vernet’s family of painters was born. Horace Vernet was welcomed in June 1789.

Changing Times:

The families still lived in the Louvre, but tragedy was fast approaching. Anxiety was mounting, especially around and within the royal palace. In the summer of 1789, the cafés became crowded, with Café de Foy known as a small capital of agitation in the kingdom. A political club often held meetings at Café de Foy, where speakers disturbed or influenced the regular visitors. Whether Carle Vernet was present on July 12, 1789, is unknown, but it is very likely.

Only a few months later, in December, Carle lost his father Joseph, the great painter who had just had time to see his grandson Horace. Until then, the artists seemed to have been spared from troubles, but this was about to change rapidly. The free lodgings they occupied appeared to arouse considerable jealousy. Perhaps this is why, in March 1790, Carle sent a note requesting confirmation of his lodging certificate. That same year, Carle became a captain in the Royal Guard. As far as sources inform us, Carle never became deeply involved in politics, but the events seem to have pushed him to side with the French revolution. Other sources suggest that Carle, unlike Moreau his father-in-law, remained a royalist. In his account book, now kept at the Museum Calvet in Avignon, Carle purchased cockades as early as April 1789. The tricolour cockade became the official symbol of the revolution in 1792. As a painter, however, Carle often had to acquire different pieces of clothing. He regularly paid models, and they had to be dressed with extras, which was quite common in those days. However, this does not prove that Carle sided with the French revolution, at least at such an early stage.

In August 10, 1792, Carle was on guard at the Tuileries when an unexpected and very sudden fight started. He immediately understood that this uproar was quickly going to get out of hand. This day later became known as a historic event The Storming of the Tuileries with Carle present at the very beginning. Like many women, Carle’s wife had already donated her jewels to the nation, but it was also well known that the Vernets had a strong connection with the royal family.

Anyhow, Carle was not reassured about his family. Probably panicking after hearing the noise of the crowds outside, he decided to leave immediately. Both he and his wife took two horses along with their young children, Horace and Camille, hoping to ride to safety. Carle quickly removed his national guard uniform, keeping only his white jacket with a red collar. Fortunately, the Republicans mistook him for a Swiss. However, during their escape, Carle was shot at. His hand got injured but the injury did not stop them from galloping to safety at the home of Moreau, the children’s grandfather, where they could all recover from everything that has happened to them.

Carle’s Position towards the French Revolution, with or against?

This question remains difficult to answer due to the lack of supporting documents. Carle lived in the Louvre, like many other artists, with the Palais Royal located just behind it. We know he was most likely present at the Café de Foy, where many political meetings took place, and he was enthusiastic about new ideas. On the other hand, both father and son, Joseph and Carle, were part of the elite hosted by the King, and Carle was a captain in the Royal Guard. He also donated to the Jacobins, subscribed to the Journal Des Débats, and purchased ribbons for cockades.

An unpublished document dated 1815 was discovered much later. The author Charles Philippe of France was brother of King Louis XVIII, and later become King Charles X in 1824. The document is a diploma, awarded to Carle Vernet, mentioned all his previous roles: painter, grenadier sergeant, member of the National Guard, and appointed painter of the War Depot in 1804 during the reign of Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte. Carl had served in the National Guard since February 1814. That same year, he was granted the right to wear the decoration of the Fleur-de-Lys. The decoration was described in detail as a silver Fleur-de-Lys surmounted by the Royal Crown all in silver. It seems strange to think that such a diploma could be awarded to a revolutionary. Was he still a royalist at heart? Either way, there is no conclusive evidence.

The years of Le Terreur:

Le Terreur (as the French revolution was described) was rapidly approaching. The artists managed as best they could, but commissions were scarce. Carle’s inherited fortune appeared to be dwindling quickly. As rumours grew louder, Carle urged his sister to stay in Paris and offered for her to come live with him, believing she would be safe. Unfortunately, it turned out she was not. More and more people found themselves imprisoned without ever knowing the reason and without the ability to defend themselves. As soon as Carle heard that his sister was taken from the house and falsely accused, he rushed to the home of the painter Jacques-Louis David, whom he considered a good and loyal friend and Carle knew to had been an admirer of his sister. A single word from David to either Robespierre or Danton could have saved her life. But David refused to help or refute that the accusations. It was well known that David was very interested in the pretty Émilie and had even painted her, but she was not interested in him. In her case, the rejection meant a horrific end of her life. Émilie Chalgrin-Vernet, at 34 years of age and a mother of a child, was executed by the guillotine on July 24, 1794. Long after Carle had lost his little sister, he fell into a gloomy silence, mixed with dark rage whenever the name David was mentioned.

Three years later, in 1797, Moreau, Carle’s father-in-law, took up a teaching position at the Écoles Centrales. This role allowed him to see many students pass through his ranks, including his own grandson, Horace Vernet. To pass a test at this school, Horace painted a galloping rider firing a shot on a small box. Was this choice inspired by the memory of having to leave the Louvre when he was a very young child? Or was it because his father, Carle, had accumulated many weapons and uniforms in their home to serve as accessories for his paintings? This collection once led to a near-fatal accident: Horace and his young friends had constructed an improvised cannon, which exploded. The noise was so loud that people initially feared an attack. Carle was furious and took measures to prevent such incidents from happening again. Fortunately, Horace only had a lock of hair singed. Another anecdote about Carle involves horse racing. Between 1795 and 1798, festivals were often held to celebrate Liberty, during which horse races were organised. Carle also competed, placing second on at least one occasion, and the first sometime later.

Return of Peace and a Taste for Life:

The year 1800 finally brought peace to the country, and at the same time, the idea of grandeur, conquests, and victories enthralled the entire population. The Parisians rediscovered their zest for life and the desire to go out and make their mark.

Carle also regained his full stature. This time, he did not change his style but his subject. The Café de Foy still operated by the Jousserand family. The regular patrons remained loyal, and Carle visited every evening to meet with his circle of friends, often bringing his 11-year-old son Horace with him. During the same period, Napoleon stored the numerous works from his campaigns at the Louvre, which soon led to a serious lack of space. The galleries were still occupied by artists, but the idea of sending them away began to take hold. Finally, in 1806, Napoleon expelled everyone, and all the artists had to find new homes. The Vernets settled on Rue de Lille, not far from the Louvre, where they would remain for the next 44 years. Since then, the famous Louvre became a national museum.

Carle, now working for Emperor Napoleon, began painting more battle scenes, which naturally included many horses—at Napoleon’s own request no doubt. His first painting, The Battle of Marengo, was a most beautiful composition. In 1808, Carle exhibited the painting Morning of the Battle of Austerlitz at the Salon. This work was highly praised and earned him the Cross of the Légion d’Honneur. Napoleon personally presented the award to him, saying the following:

“Monsieur Vernet, you are like Bayard—without fear and without reproach. This is how I reward merit! It did not end with the Emperor’s words.”

Empress Josephine said to Carle Vernet:

“These are two crosses in one. There are men who carry a great name; you, Sir, bear yours.”

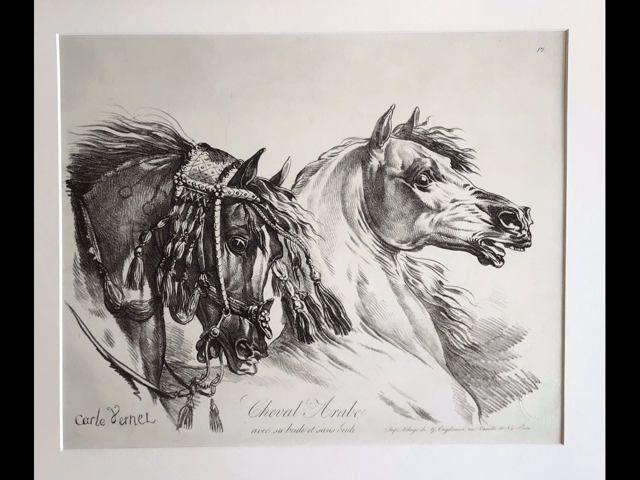

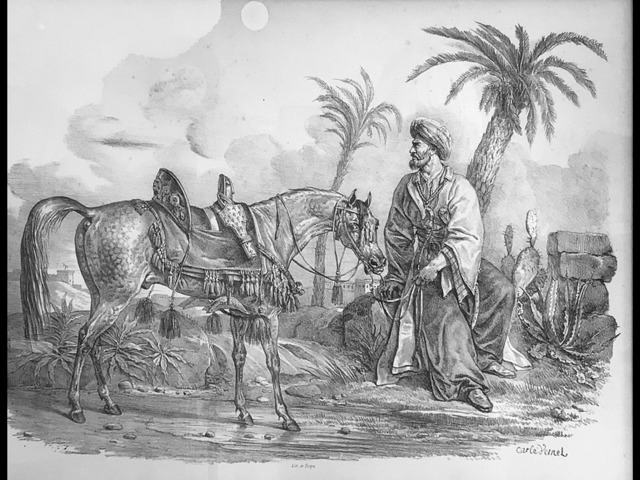

Carle Vernet and the Mamluks:

Carle also painted the Mamluks on many occasions, not because he had travelled to Egypt, but because the Mamluks had become a very popular subject in French art and culture following Napoleon’s Egyptian campaign between 1798 and 1801. The invasion of Egypt introduced the Mamluks, a warrior class, to the French public’s imagination. After the Battle of the Pyramids in 1798, where French forces defeated the Mamluks, they became symbols of bravery and noble warriors in the eyes of the French. This made them an ideal subject for painting.

Carle was already famous for painting military scenes and horses. The Mamluks, being highly skilled horsemen and known for their spectacular, ornate costumes, fit perfectly into his artistic interests. This was not the only reason, however. Paintings of the Mamluks served to glorify Napoleon’s campaigns and celebrate the Empire. Some Mamluks even joined Napoleon’s army, either voluntarily or out of political pragmatism, becoming part of an elite cavalry and bodyguards. They were known as the Mamluk Squadron of the Imperial Guard and fought in several major European battles. This may explain why several saddles and bridles ended up in the Musée de l’Armée, located just next to Napoleon’s grave in Paris.

Carle Vernet The Teacher:

Like all renowned painters, Carle had a studio where he taught -and like his father Joseph, he had a big and generous heart for his pupils. He often paid for the first works of many of his students to encourage them to continue their efforts. In 1808, a young man of only seventeen years arrived at the studio of his first teacher, Carle Vernet. His name was Theodore Géricault (1791–1824). He not only learned to paint but also shared his teacher’s passion for the world of horses. Géricault also spent some time in Rome. When he returned in 1817, he rented a studio on Rue des Martyr, next to his friend Horace Vernet, the son of his master. It was Carle Vernet who introduced his young student, Géricault, to Freemasonry. Géricault later painted a portrait of Louise, the daughter of Horace, who had married Louise Pujol in 1810.

The young Duke of Orleans often visited Horace. The Duke, Louis-Philippe, was the future King of France. It was during these visits that he met Lami, one of Carle Vernet’s pupils. Lami later became an official painter at the Royal Court.

Although Carle had been an approved member since 1789, he was not able to enter the Académie des Beaux-Arts until 1816.

There are several anecdotes about Carle, who was always ready to laugh and joke, even about serious matters. One day, he was stopped by thieves near the stock exchange. They demanded that he hand over his money immediately or they would take his life. Carle replied: “The stock exchange is at the end of the street, and my advice to you is to change your profession as soon as possible.” No doubt Carle had wit, but not everyone liked his jokes. Empress Josephine did not find them very amusing; she even wrote a letter to Carle, describing him as a very interesting man but criticising his jokes as being of poor quality and overly repetitive.

In 1811, the Ministry of the Armed Forces sought to completely revise the military uniform. Carle was commissioned to create miniature figures representing the branches of the army, resulting in a total of 244 plates entitled The Grand Army of 1812.

Carle Vernet and Lithography:

Lithography was a new printing process that used a soft limestone sourced from a mine in Solnhofen, Germany. The process was invented by Alois Senefelder in 1796 and was soon adopted by many French artists. Carle was certainly one of the first to utilise this innovative technique. However, once the lithographs were made, often no more than around 60 prints were produced, especially from the very large stones. Afterward, the stone had to be cleaned so it could be reused to create a new image and print. This also meant that the previous image on the stone was lost forever.

Around that time, Carle became friends with Louis Debucourt (1755–1832), a painter and renowned engraver whom he often met at the Café de Foy. Debucourt ultimately engraved nearly 80 pieces of art created by Carle Vernet. There is no doubt that these were among the most beautiful works.

From 1820 to 1824:

In 1820, Carle returned to Rome with his son Horace. The trip was short but Horace’s personal notes indicated that they were warmly received in the city. After all, their grandfather Joseph had lived there for 20 years and was well remembered.

One year later, Carle received the Medal of the Grand Gordon of Saint-Michel for a painting titled The Dog of the Duke of Enghien. At the same time, his son Horace became a member of the Institute. This marked the first time in history that three successive members of the same family were welcomed into the Institute. Horace was painting seascapes, horses, and military scenes at the time, but he was also deeply committed to liberal and Bonapartist ideals. He presented a series of canvases at the Salon of 1822 that reflected his political beliefs. Although these were rejected by the Salon, the public exhibition he held in his studio was a great success.

In 1824, during the reign of King Charles X of France, a grand ceremony was organised in which all the renowned painters were invited to receive medals. We know of this event from a painting by François-Hippolyte Heim, housed at the Louvre, where both Carle and his son Horace Vernet were to receive their awards.

The year 1824 was also the year the great painter Théodore Géricault died a few weeks later because of injuries he sustained from falling off the back of a horse. Géricault was undoubtedly one of the most important painters of the 19th century. He was buried at Père Lachaise Cemetery, and many of his friends contributed to the cost of his grave. Carle lost his famous pupil, and Horace lost one of his closest friends.

Carle and Horace Vernet were both invited and are visible in this painting.

The Return to Avignon (1826–1836):

In 1826, father and son Vernet received an important invitation. In Avignon, Joseph’s hometown, the city council wanted to develop the Calvet Museum by adding a gallery dedicated to painting. The Académie du Vaucluse decided to launch a competition in Joseph’s honour. His son and grandson were invited to participate in this tribute. Moved and grateful, Horace even expressed the wish to take the entire Vernet family to Avignon to attend the celebration honouring his famous father and grandfather. That year, Carle received 2,000 francs from the Calvet Museum, initially for a painting of a Cossack; however, this was later changed to a painting titled The Riderless Horses. These types of races were very popular in Rome, and many painters attempted this subject. Horace chose Mazeppa with the Wolves which was an equally popular theme to paint at the time. The exact circumstances are somewhat unclear, but the date of departure to Avignon changed several times. Due to the extended preparation period, the Calvet Museum acquired two additional paintings.

When they finally set out for Avignon, the journey took some time, with several stops along the way. One stop was Lyon, followed by Château de Montfauçon, and they traveled slowly to their destination, finally arriving in Avignon on October 8, 1826. Apparently, these changes of dates had not upset the people organising the event, as they were warmly welcomed and the festivities soon began.

The opening of the new galleries took place four days after their arrival. First, there were all kinds of festivities, speeches, and poetry readings, which lasted several days. They were also invited to the Franconi Circus. Over the years, the horses had often served as models for Carle. This circus was very famous for its equestrian displays. A painting by Joseph Vernet was the centrepiece of the gallery’s official opening. The organization also commissioned a medal featuring a bust of Joseph Vernet. The names of all three generations of the Vernet family were engraved on the back. The only gold copy of this medal was presented to the Duchesse de Berry during a visit in 1829. The festivities lasted several days following the grand opening and included a ball. A local newspaper mentioned Carle as follows: “The well-known painter Carle Vernet (69 years old) was noted for the nobility and lightness of his dancing.”

On October 17th, the Vernet family returned to Paris. That same year, Carle also received a medal in his honour. After returning to Paris, Carle continued his work as usual until two years later, when Horace changed his career. This career change took him to Rome, where in 1828 he was appointed director of the Académie also known as The Villa Medici in Rome. His father decided to follow him. Shortly after Horace’s departure, Carle left as well, taking his granddaughter Louise, who was 15 years old, and his daughter-in-law with him. The Vernet family stayed in Rome until January 1, 1835, when Horace Vernet was succeeded by the painter Jean-Auguste Ingres (1780–1867).

During their seven years in Rome with Horace serving as Director of this Académie, many famous people came to visit. Hector Berlioz (1803–1869), the renowned French composer, visited Rome in 1831 and 1832. Berlioz was enchanted by the young Louise Vernet, who played the piano exceptionally well, as mentioned in a letter he wrote. Father Horace and grandfather Carle attended several operas together with Berlioz during his visits.

The German composer Felix Mendelssohn (1809–1847) also spent time at the Villa Medici and was charmed by the young Louise. In a letter, Mendelssohn described the Vernet family as being very skilled dancers and was impressed by the respectful way Carle spoke of his late father. Horace created a wonderful portrait of the young Mendelssohn, which is now owned by the British Museum.

In 1830, the peaceful days were disrupted when the Revolution forced the Vernet family to seek refuge in Naples for a time, leaving Horace in charge of The Villa Medici. Unfortunately, in a changing Italy, the French were not as well liked as before.

Just before reaching this refuge, Dr. Biet came to inform Carle that the King wished to award him the rank of Officier de la Légion d’Honneur. Carle’s reply:

“I appreciate the honor, which I attribute not so much to my own merits as to the good fortune of being the son and the father of two great artists.”

In 1835, Louise Vernet married the painter Paul Delaroche. Louise had two sons, Horace and Philippe, before she died in 1845 at only 31 years old.

In 1936, when Horace had just left for Russia, where he was welcomed by Emperor Nicholas, he was summoned to return to Paris immediately. His father had fallen gravely ill, although even shortly before his death, Carle was still riding in the Bois de Boulogne, where even young riders struggled to keep up with him.

On November 19, 1836, Carle spent his last evening at Foy’s Café, where he was the oldest and most loyal customer. He made jokes there as usual, but since it had rained all day, his clothes became soaked, and he caught a chill. He died from pneumonia only eight days later at his home in Paris. A major celebration in his honour was organised by the prominent Masonic Lodge, the Nine Sisters. As Carle was also a member of the Royal Academy of Fine Arts, a tribute was delivered by one of its members. His hearse was drawn by six horses. Carle Vernet was buried at the Cimetière de Montmartre in Paris, where his son Horace, who died in 1863, also found his final resting place.

Carle once said:

“I am the son of a king and the father of a king, but I was never a king myself.”

Looking back on his life, works, and achievements as a teacher, the author realises that these words were not entirely true.

© Claudia Dijkstra Crommelin. 2025. All rights reserved.

Bibliography:

L’Oevre de Carle Vernet, by Paul Colin, éditions de la galerie Giroux, Bruxelles. Collection de Rosen, la vente avril 24 et 25, 1923. The sales catalogue gives detailed descriptions of 230 works by Carle Vernet.

Larousse du XX siecle, published 1933.

Une Famille d’artistes : les trois Vernet : Joseph – Carle – Horace, by Charles Blanc, published 1898.

Blanc, a member of L’Académie Française et de L’Académie des Beaux-Arts.

Horace Vernet, édition Cháteau de Versailles, 2023.

Les Chevaux de Géricault, Musée de la Vie Romantique, Paris, 2024.