The Horse in New Kingdom Egypt is an indispensable book to anyone who wants to learn about horses in ancient Egypt. It is a PhD dissertation by Dr. Susan Turner, which she has dedicated to the study of ancient Egyptian horses.

In this article, I’ll be sharing with you the part she dedicated to the study of the skeletons and what the findings tell us about the morphology and breeds of the horses that entered Egypt and formed its foundation stock.

According to Turner, several challenges hindered the study of the Egyptian horse. Most research has primarily focused on chariots rather than the horses themselves. A second challenge is that excavations were predominantly aimed at exploring human history, which resulted in the excavation of tombs and settlements rather than sites relevant to equine history. The third challenge is the lack of expertise in zooarchaeology, which has affected the study of the Egyptian horse, particularly in distinguishing horse remains from those of other equids. The fourth challenge is the poor condition in which some samples were preserved. Lastly, the looting of tombs with sharp tools has led to the destruction of valuable bone remains.

Source: Wikipedia

Turner discusses the hypotheses that have influenced the study of the Egyptian horse. The first is the ‘indigenous’ hypothesis, while the second pertains to the origins of the Arabian horse. The idea that horses were indigenous to Egypt emerged in the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries, drawing on ancient historical texts such as those by Plutarch and Manetho, as well as biblical references and some preliminary archaeological findings. Scholars such as Gabriel Fabricy (in 1764), Chabas (in 1873), and J. Capart (in 1938) advanced the ‘indigenous’ theory. However, this hypothesis has been thoroughly rebutted and is now considered obsolete by modern Egyptologists. The technological advancements required by World War I and World War II have positively impacted many scientific fields, including archaeology. Furthermore, new methodologies in Egyptology have been developed, leading to innovative approaches in studying the history of ancient Egypt. As for the the origins of the Arabian horse, scholars searched for the origin of this breed in numerous locations and monuments including Egypt which acted a distraction to studying the Egyptian horse independandtly. In her PhD, Turner focuses on the study of the Egyptian horse, its origin, morphology, impact on Egypt and the life of Egyptians.

Source: The Metropolitan Museum

Turner discusses the hypotheses that impacted the study of Egyptian horses. The first being the ‘indigenous’ hypothesis, and the second hypothesis concerning the origins of the Arabian horse. The hypothesis that horses were indigenous to Egypt developed in the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries based on ancient historical texts such as Plutarch, Manetho, and biblical texts, in addition to some preliminary archeological findings. Scholars such as Gabriel Fabricy (in 1764) Chabas (in 1873) and J. Capart (in 1938) advanced the ‘indigenous’ theory. This hypothesis has been completely rebutted and deemed obsolete by modern Egyptologists. The technological advances that World War I and World War II demanded have positively impacted many fields of science, including archeology. Additionally, new methodologies in Egyptology were developed, leading to a new approach in studying the history of ancient Egypt.

Research on Egyptian horses has been influenced by inquiries into the origins of the Arabian horse. Scholars have sought answers regarding the Arabian horse’s lineage in various locations and monuments, including Egypt. In her PhD dissertation, Turner concentrates on the study of the Egyptian horse, examining its origins, morphology, impact on Egypt, and the lives of the Egyptians.

Source: The Metropolitan Museum

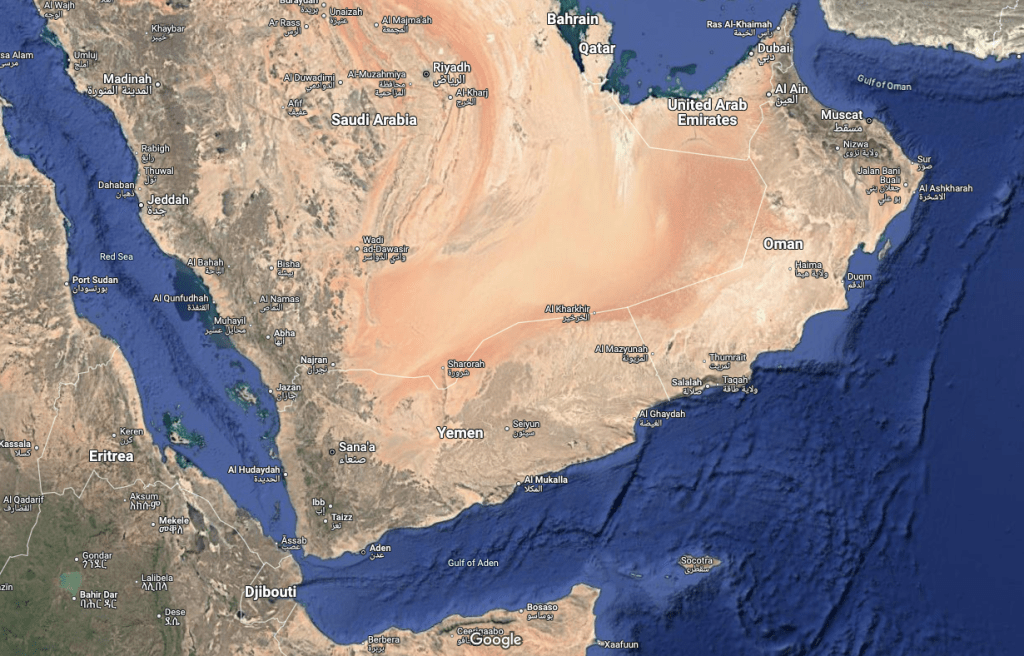

Tuner discusses the journey of horse domestication in the area stretching from Ukraine to the Caucasus, then the spread of horses and horse culture towards the South West until horses arrived in the Nile Valley in the Late Second Intermediate Period (SIM spanned from about 1700 to 1550 BC). You can read Part I of my article to learn more about it. It took the horse 500 years to journey from the Caucasus to the Nile Valley.

The Late Second Intermediate Period is marked by the migration of the Asiatics, known as Hyksos, to Egypt, to whom scholars attribute the introduction of horses and horse culture to the Egyptians.

The migration of the Hyksos or Asiatics to Egypt was a long and slow process due to the need of the Egyptians for human resources in different sectors. Eventually, they established the 15th and 16th dynasties and took control of Lower and Middle Egypt. Turner traces the origin of the Hyksos to Northern Levant. It is the area in which the textual, archeological and osteological evidence attest to the presence of horses and horse culture. It is the region that was influenced by the Amorites and Hurrians, who established the horse cultures prior to the Egyptians. Turner confirms that to date (the date of writing the thesis) there is not a single osteological evidence that supports the presence of horses Egypt before the Hyksos’ migration from Syria-Palestine which is around 1750 BC. While the textual and iconographic evidence date from later 17th and early 18th dynasties.

Source: Wikipedia

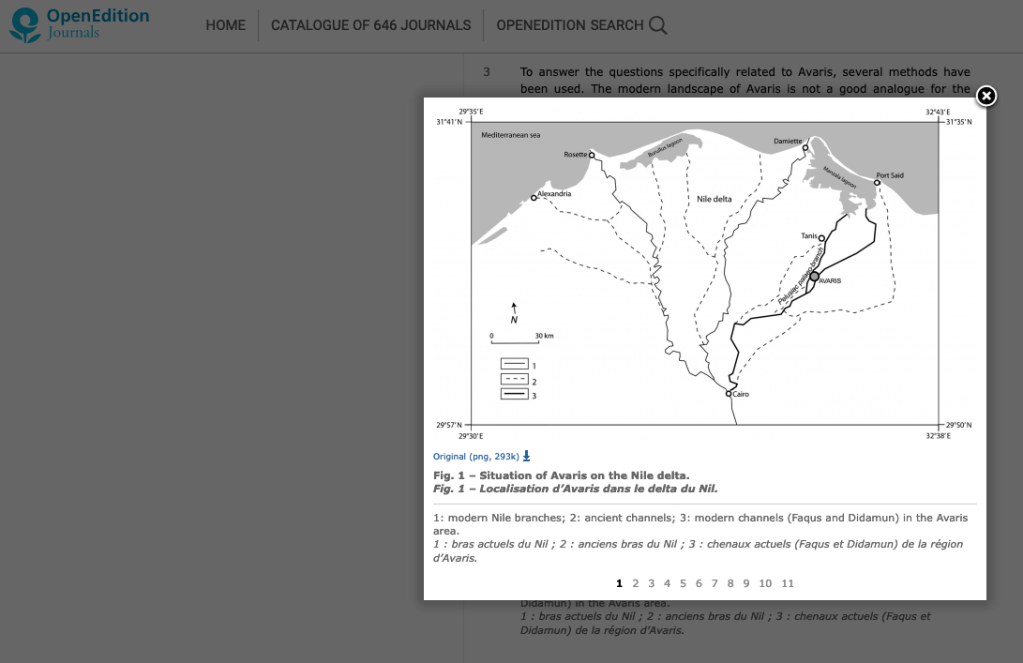

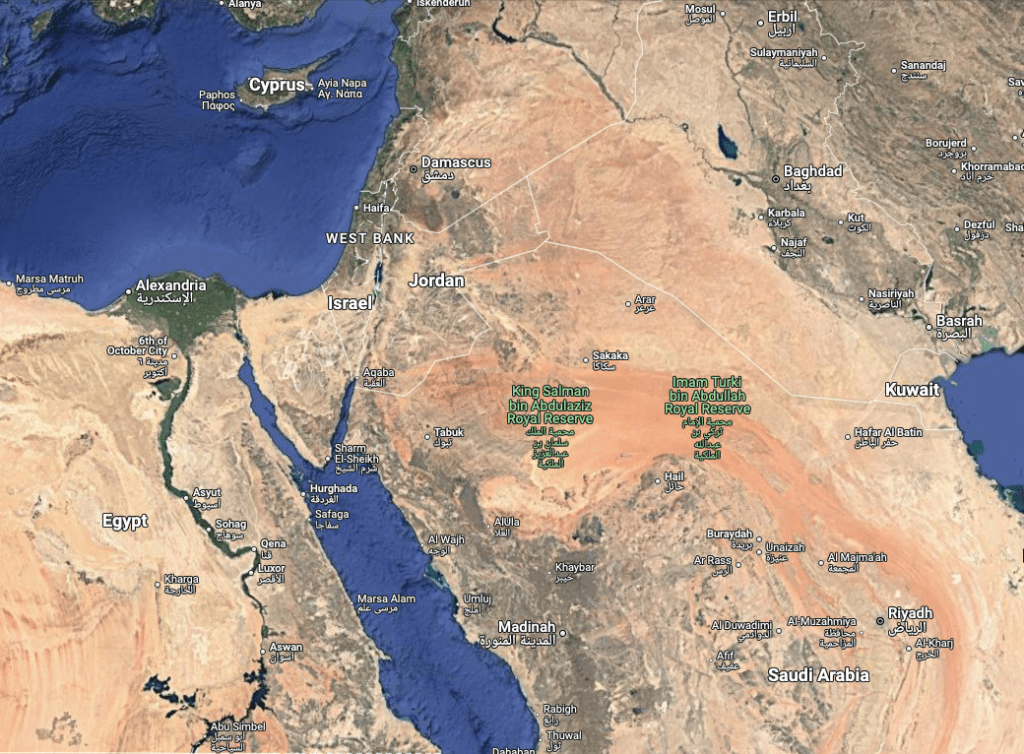

Other scholars suggest that trade (direct and indirect) contributed to the introduction of horses and horse culture to the Egyptians. There were three major trade routes that channeled traffic from the Levant and the Arabian Peninsula to Egypt.

The first one is directly by sea from the Levant to Egypt. The second route starts by the coastline then into the Pelusiac branch of the Nile towards Avaris or Tel al-Dabaa, capital of the Hyksos. The third route received traffic from Southern and Northern Arabian Peninsula then channeled the traffic into the Delta through Wadi Tumailat where Tel al-Mashkouta is located, the latter an important excavation site in which horse skeletons were found.

Source: Open Edition.

Source: Google Maps.

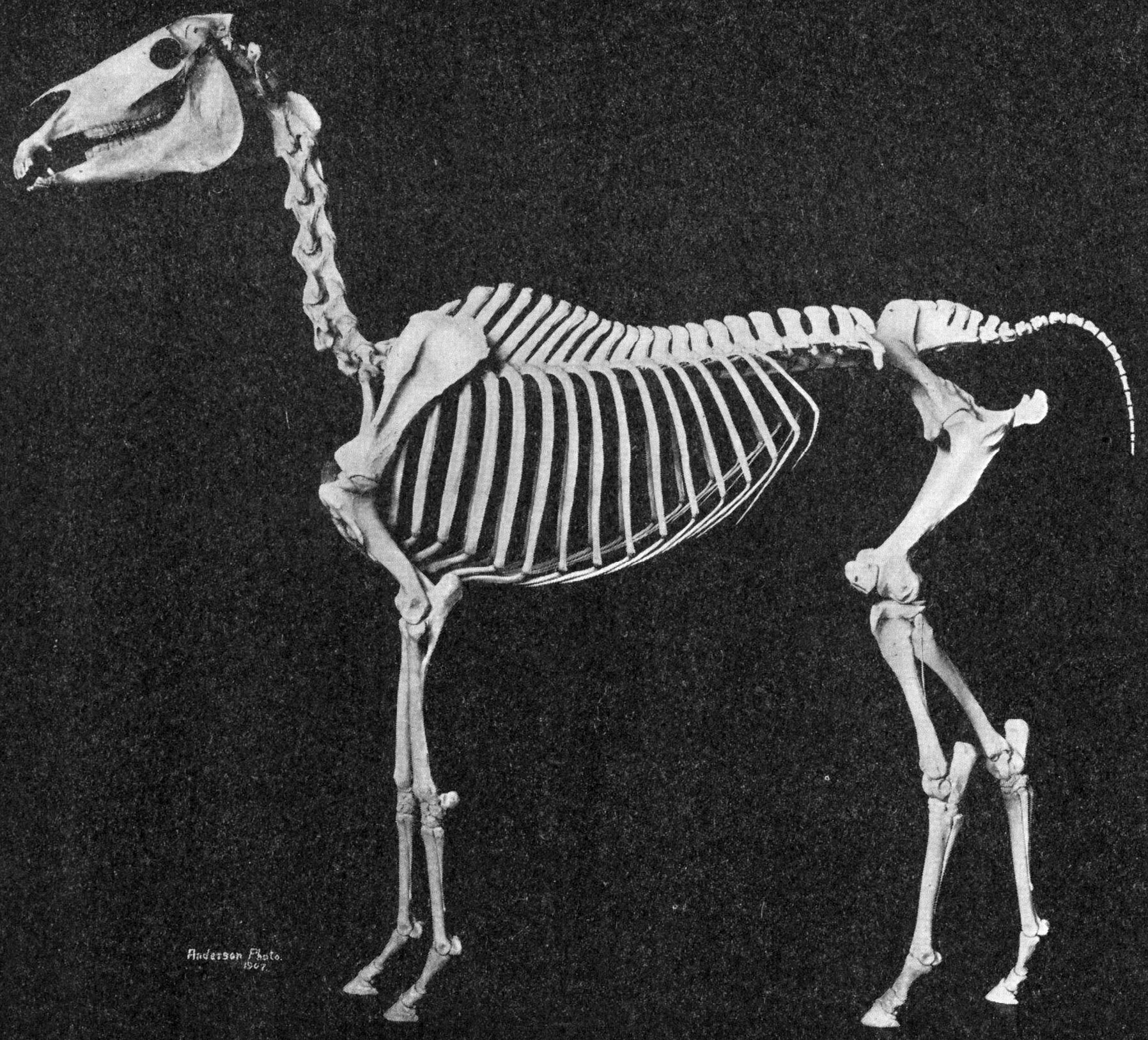

The oldest evidence for the presence of horses in Egypt is approximately 1750 B.C. The samples examined range from complete skeletons to teeth and canines. From the period 1750 to 1120 B.C., 21 sets of remains were found. The majority are dated to the period spanning from 350 to 600 B.C.

There were two morphological types that were present in Egypt and Nubia. The first type is a small and refined type, demonstrating similarities with the Arabian horse breed. The other type is characterized by large and heavy features. The two osteological samples in Der el-Bahari and Soleb confirm the 5 lumbar vertebrae, a characteristic peculiar to the Arabian horse. However, Turner states that “there is far too little external material, which is in too poor a condition to allow any speculation concerning the breed to which it might belong or to which it may have been the progenitor.“

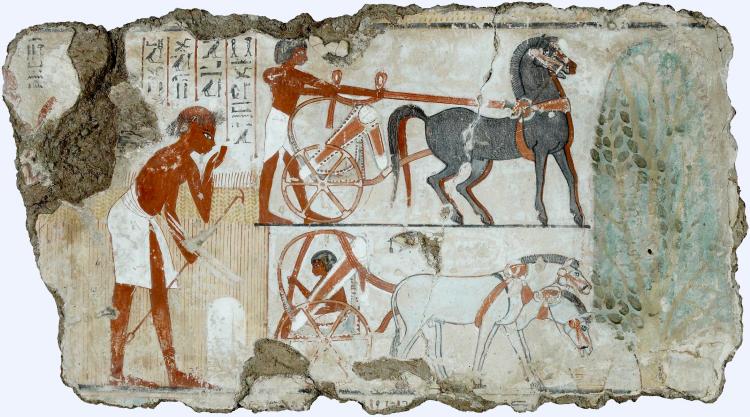

Offerings of a Chariot and Horse, Tomb of Userhat, ca. 1427–1400 B.C.

Egyptian, New Kingdom

Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Source: Wikipedia.

Tel El-Kebir Sample: Unfortunately, the bones have not yet been confirmed to belong to a horse. Turner says that in 1994, Dr. A. Hassan of EAO announced that a tomb near Tel el-Kebir contained two horse skeletons. He dated them to approximately 1750 B.C. Scholars mentioned that they have no knowledge of them, and Dr. Hassan has not been contactable to give more information on the skeletons. Thus, it is believed that the skeletons have been misidentified and might be regarded as those of donkeys.

Buhen Sample: It is a nearly complete skeleton dated to 1675 B.C. that is large in size (possibly due to castration) and is considered the earliest evidence of the return of horses to Africa. The Buhen fortress was constructed by the kings of the 12th dynasty to safeguard Egypt’s southern borders and to exert control over the lower Nubian territory. Boekoenyi stated that the horses of Egypt originated from an Eastern group (or Oriental Horses), which included Egyptian Buhen, Hittite, and likely later Mesopotamian horses. They resembled the Arabian breed and belonged to the group of horses depicted in 18th dynasty iconography. Boessneck observed the similarities between the Buhen sample and the later Theban horse, noting that they closely resemble the Hittite horses excavated at Osmankaya in central Anatolia. He stated that these horses are identical in size. Turner finds Boessneck’s observation is not surprising, considering that Anatolia served as one of the key ‘stops’ in the journey of horses from the Eurasian Steppes to Egypt.

Tel el-Dabaa (Avaris) Sample: It is the oldest and largest excavation site, as it was the capital of the Hyksos. This site provides evidence that horses first entered Egypt between 1750 and 1700 B.C., predating the Buhen horse. One of the samples discovered is a complete skeleton featuring a stocky skull and convert arched nose.

Deir al-Bahari, Thebes Sample: An examination of the skeleton was conducted in 1937, suggesting that it indicated an Arab type. However, in 1969-70, Boessneck reexamined the remains, and the measurements of the bones revealed a horse larger than previously believed. This horse corresponds to the type depicted in New Kingdom representations (circa 1550 – 1070 B.C.) and is comparable in size to the Hittite horse from Osmankaya in central Anatolia.

Sai Sample: Say is an island located in northern Sudan. The sample dates back to the beginning of the New Kingdom. The skeleton an African horse.

Tel Heboua Sample: The sample of a complete skeleton dates back to the end of the Second Intermediate Period and the very beginning of the New Kingdom. This specimen is of a horse that had a heavy head, large teeth, and robust distal limbs. This sample represents another type of horse that contributed as foundational stock to the breeding of the Egyptian horse.

Photo credit: Rania Elsayed

Soleb Sample: Soleb is located in northern Sudan. The skeleton was discovered in a cemetery dating back to the time of Amenhotep III. The horse was small in size, with a small skull, a short muzzle, and sturdy legs.

Kurruh Sample: Kurruh is an excavation site located in northern Sudan, specifically within the cemeteries of Kush. The sample size is significantly larger than that of the average Oriental horse.

Saqqara Sample: Saqqara necropolis is located in the Giza Governorate. Three skeletons dating to the 20th Dynasty of the Ptolemaic period were discovered. One complete skeleton represents the Barb or North African type.

From the Late Second Intermediate Period and onwards, the size and number of horses in Egypt and Nubia increased, indicating either a deliberate breeding strategy or the importation of horses larger in size.

Until Part IV of this series!

Source: The Metropolitan Museum